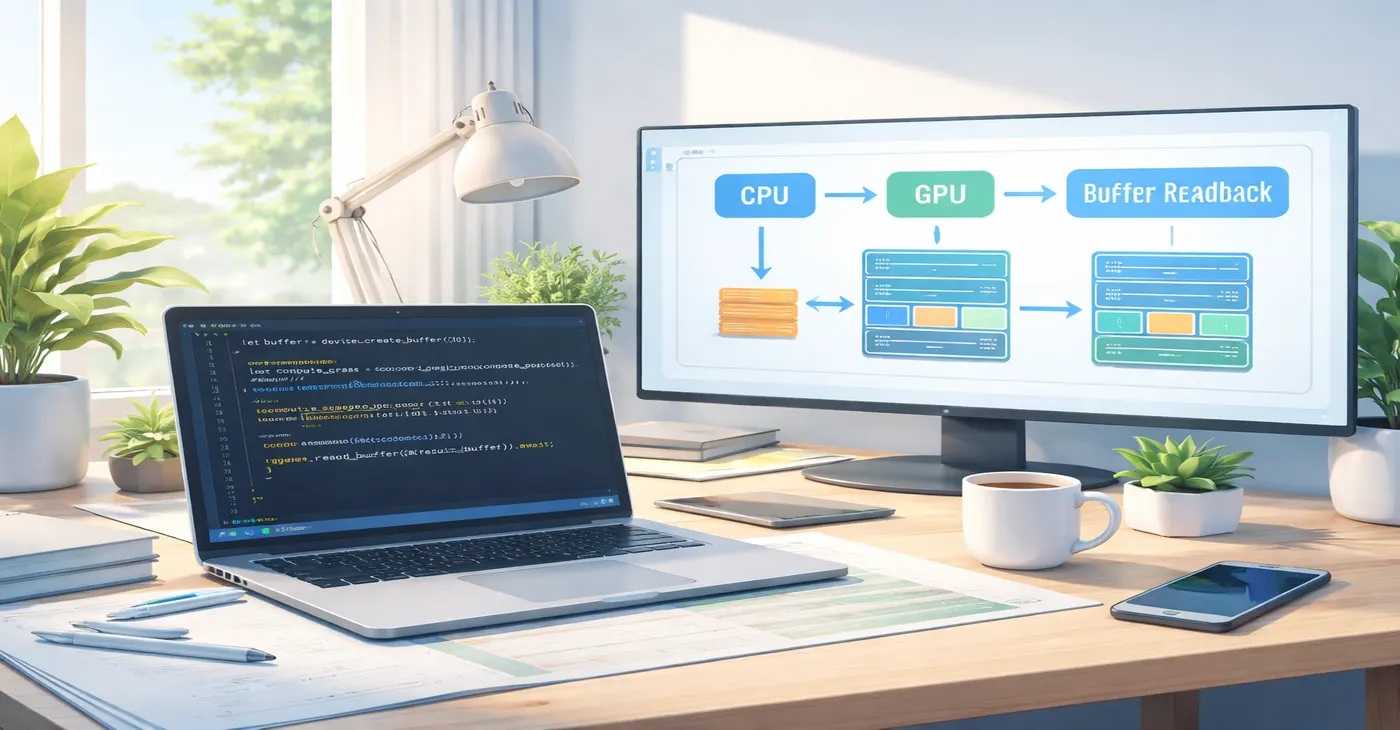

GPU computing is no longer the exclusive territory of CUDA or OpenCL. With the arrival of wgpu, Rust developers now have a safe, cross-platform, and portable way to run massively parallel workloads on the GPU. Whether you are targeting Vulkan on Linux, Metal on macOS, DirectX 12 on Windows, or even WebAssembly in a browser, wgpu compute provides one consistent API that works everywhere. This article walks you through a minimal working example of wgpu compute in Rust, explains how buffer readback works in detail, and shares practical performance tips drawn from real usage patterns.

What Is wgpu and Why Use It for GPU Compute in Rust

wgpu is a safe, pure-Rust graphics and compute API based on the WebGPU specification. It runs natively on Vulkan, Metal, DirectX 12, and OpenGL ES, and it also compiles to WebAssembly for browser targets using WebGPU or WebGL2. Because it is written in Rust and embraces the language ownership model, it avoids entire classes of bugs common in lower-level GPU APIs like raw Vulkan or CUDA C. The API is built around a few central objects: the Instance, Adapter, Device, Queue, and various resource handles like buffers and pipelines. When you want to do wgpu compute work rather than drawing pixels, you create a compute pipeline instead of a render pipeline. The shader language used is WGSL, which stands for WebGPU Shading Language, a modern, type-safe shading language designed specifically for GPU programs.

The biggest advantage of using wgpu for GPU compute in Rust is portability combined with safety. You write the code once, and it runs on essentially every GPU and platform in use today. The Rust host code benefits from the borrow checker and strong type system, while the WGSL shader code runs on the GPU.

Setting Up the Project

Start by creating a new Rust project and adding the wgpu dependency to your Cargo.toml. You will also need the pollster crate to block on async calls in a simple main function, and bytemuck for safe byte casting of data buffers.

[dependencies]

wgpu = "22"

pollster = "0.3"

bytemuck = { version = "1", features = ["derive"] }

wgpu minimum supported Rust version as of 2025 is 1.87 for the wgpu crate itself. Keep your Rust toolchain updated to avoid compiler compatibility issues.

A Minimal wgpu Compute Example in Rust

The following example demonstrates the simplest possible wgpu compute program. It uploads an array of floating-point numbers to the GPU, runs a WGSL compute shader that multiplies each element by two, then reads the results back to the CPU using buffer readback. Every step is explained so you understand what is happening at each stage of the GPU pipeline.

Writing the WGSL Compute Shader

The shader is the code that actually runs on the GPU. Save this as shader.wgsl in your src directory:

@group(0) @binding(0)

var<storage, read_write> data: array<f32>;

@compute @workgroup_size(64)

fn main(@builtin(global_invocation_id) gid: vec3<u32>) {

let index = gid.x;

data[index] = data[index] * 2.0;

}

The @group(0) @binding(0) annotation connects this buffer variable to binding slot zero of bind group zero in the wgpu pipeline. The @compute @workgroup_size(64) annotation marks this as a compute shader entry point and sets the workgroup size to 64 threads. Each invocation receives its global x-coordinate through the builtin global_invocation_id, which it uses as an array index. The shader doubles each value in place.

The Rust Host Code

The following is the complete Rust host code to drive this wgpu compute shader:

use wgpu::util::DeviceExt;

fn main() {

pollster::block_on(run());

}

async fn run() {

// 1. Initialize wgpu

let instance = wgpu::Instance::default();

let adapter = instance

.request_adapter(&wgpu::RequestAdapterOptions {

power_preference: wgpu::PowerPreference::HighPerformance,

compatible_surface: None,

force_fallback_adapter: false,

})

.await

.expect("No suitable GPU adapter found");

let (device, queue) = adapter

.request_device(&wgpu::DeviceDescriptor::default(), None)

.await

.expect("Failed to create device");

// 2. Prepare input data

let input: Vec<f32> = (0..256).map(|x| x as f32).collect();

let data_bytes = bytemuck::cast_slice(&input);

// 3. Create a GPU storage buffer with the input data

let storage_buffer = device.create_buffer_init(&wgpu::util::BufferInitDescriptor {

label: Some("Storage Buffer"),

contents: data_bytes,

usage: wgpu::BufferUsages::STORAGE | wgpu::BufferUsages::COPY_SRC,

});

// 4. Create a staging buffer for readback

let staging_buffer = device.create_buffer(&wgpu::BufferDescriptor {

label: Some("Staging Buffer"),

size: (input.len() * std::mem::size_of::<f32>()) as u64,

usage: wgpu::BufferUsages::MAP_READ | wgpu::BufferUsages::COPY_DST,

mapped_at_creation: false,

});

// 5. Load shader and create compute pipeline

let shader = device.create_shader_module(wgpu::ShaderModuleDescriptor {

label: Some("Compute Shader"),

source: wgpu::ShaderSource::Wgsl(include_str!("shader.wgsl").into()),

});

let pipeline = device.create_compute_pipeline(&wgpu::ComputePipelineDescriptor {

label: Some("Compute Pipeline"),

layout: None,

module: &shader,

entry_point: Some("main"),

compilation_options: Default::default(),

cache: None,

});

// 6. Create bind group

let bind_group_layout = pipeline.get_bind_group_layout(0);

let bind_group = device.create_bind_group(&wgpu::BindGroupDescriptor {

label: Some("Bind Group"),

layout: &bind_group_layout,

entries: &[wgpu::BindGroupEntry {

binding: 0,

resource: storage_buffer.as_entire_binding(),

}],

});

// 7. Encode and submit GPU commands

let mut encoder = device.create_command_encoder(&wgpu::CommandEncoderDescriptor {

label: Some("Command Encoder"),

});

{

let mut compute_pass = encoder.begin_compute_pass(&wgpu::ComputePassDescriptor {

label: Some("Compute Pass"),

timestamp_writes: None,

});

compute_pass.set_pipeline(&pipeline);

compute_pass.set_bind_group(0, &bind_group, &[]);

compute_pass.dispatch_workgroups((input.len() as u32 + 63) / 64, 1, 1);

}

// Copy result to staging buffer for readback

encoder.copy_buffer_to_buffer(

&storage_buffer, 0,

&staging_buffer, 0,

(input.len() * std::mem::size_of::<f32>()) as u64,

);

queue.submit(std::iter::once(encoder.finish()));

// 8. Buffer readback

let slice = staging_buffer.slice(..);

let (tx, rx) = std::sync::mpsc::channel();

slice.map_async(wgpu::MapMode::Read, move |result| {

tx.send(result).unwrap();

});

device.poll(wgpu::Maintain::Wait);

rx.recv().unwrap().expect("Buffer mapping failed");

let data = slice.get_mapped_range();

let result: &[f32] = bytemuck::cast_slice(&data);

println!("First 8 results: {:?}", &result[..8]);

drop(data);

staging_buffer.unmap();

}

If this runs correctly you will see the values 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 printed, because each of the original values 0 through 7 was doubled by the WGSL compute shader.

Understanding wgpu Buffer Readback

Buffer readback is one of the most important concepts to master when working with wgpu compute. The GPU operates in its own memory space, and you cannot simply read the output of a compute shader the way you would read a variable in CPU code. The process requires two separate buffers and an explicit copy step.

Why Two Buffers Are Needed

The storage buffer used inside the compute shader is created with STORAGE | COPY_SRC usage flags. This means the GPU can read and write it during shader execution, and it can act as a copy source. However, a storage buffer cannot be directly mapped for CPU reading unless the device supports the optional MAPPABLE_PRIMARY_BUFFERS feature, which is not universally available across all hardware.

The staging buffer is the bridge. It is created with MAP_READ | COPY_DST flags, which means the CPU can map it for reading but the GPU cannot use it as a shader storage resource. After the compute shader finishes, you use copy_buffer_to_buffer in the command encoder to transfer the result from the storage buffer into the staging buffer. This separation of roles is by design and allows the GPU driver to place each buffer in the most optimal memory location for its purpose.

The map_async and device.poll Pattern

The wgpu buffer readback flow is asynchronous. After submitting commands to the queue, you call slice.map_async on the staging buffer, which registers a callback to fire once the buffer is ready for CPU access. On native platforms you must then call device.poll(wgpu::Maintain::Wait) to drive the device event loop and wait for the GPU work to complete. Without this poll call, the callback will never fire and your program will stall. Once the callback fires, you call slice.get_mapped_range() to obtain a read-only byte slice, cast it to your target type using bytemuck, and process the data. After you are done, drop the mapped range and call staging_buffer.unmap() to release the mapping.

Performance Tips for wgpu Compute in Rust

Getting a working wgpu compute pipeline is only the first step. Getting it to run fast requires careful attention to several areas where GPU programs commonly waste time.

Choose the Right Workgroup Size

The workgroup size in your WGSL shader is one of the most impactful settings for wgpu compute performance. A workgroup is a group of shader invocations that execute together and can share local memory. The GPU hardware schedules workgroups on its processing units, and a workgroup that is too small leaves those units underutilized. A workgroup size of 64 is a widely recommended starting point for 1D compute tasks. For 2D tasks, an 8 by 8 workgroup, which is also 64 total threads, is a common default. Using the default workgroup size of (1, 1, 1) is almost always the worst possible choice for wgpu compute performance, even though it will produce correct results. Profile different workgroup sizes against your specific GPU and data dimensions, as the optimal value varies by hardware architecture.

Minimize CPU-GPU Data Transfers

The PCI Express bus that connects the CPU and GPU is orders of magnitude slower than the GPU own internal memory bandwidth. Every time you transfer data between the two, you pay a significant latency penalty. Designing your wgpu compute application to keep data on the GPU for as long as possible is one of the highest-leverage optimizations available. If you need to apply multiple compute passes to the same data, chain them together in a single command encoder submission rather than reading back and re-uploading between passes. Only perform buffer readback for the final result, not for intermediate values. This principle of reducing round-trips is more important than any shader-level micro-optimization in most real-world scenarios.

Reuse Pipelines and Bind Groups

Creating a wgpu compute pipeline involves shader compilation, validation, and driver-side work that can be expensive. If you run the same compute operation repeatedly, create the pipeline once and reuse it across multiple dispatches. The same applies to bind groups. If the buffer bindings do not change between dispatches, reuse the bind group object rather than recreating it every iteration. Recreating pipelines inside a tight loop is one of the most common performance mistakes seen in early wgpu compute code.

Use Staging Belts for Frequent Uploads

When you need to upload fresh data to the GPU frequently, such as uniform parameters that change every dispatch, using queue.write_buffer on every call will allocate a new temporary staging buffer on each invocation. For high-frequency updates, consider using a wgpu::util::StagingBelt. A staging belt maintains a pool of reusable staging buffers, reducing allocation overhead significantly when many small copies need to happen in sequence.

Prefer read-only-storage for Input Buffers

Using read-only storage for buffers that are only read in the shader allows the GPU to make further optimizations because the buffer will never be written to and does not need to be synchronized with other shader writes. In your WGSL compute shader, if a buffer is purely an input, declare it as var storage read rather than read_write. On the Rust side, declare it as BufferBindingType::Storage { read_only: true } in the bind group layout. This allows the driver to skip certain synchronization barriers that would otherwise be required for writable storage buffers.

Profile with Compute Timestamps

Before spending time optimizing shader code, measure where the time is actually going. wgpu compute supports timestamp queries through the TIMESTAMP_QUERY device feature. You can insert timestamp writes at the start and end of a compute pass by passing timestamp_writes in the ComputePassDescriptor. After resolving the query set, you get GPU-side timing data that tells you exactly how long the compute pass took on the GPU, independent of CPU overhead or driver latency. This is far more reliable than measuring wall-clock time from the Rust side.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Several errors appear consistently when developers are getting started with wgpu compute. The first is dispatching with incorrect workgroup counts. The number passed to dispatch_workgroups is the number of workgroups, not the number of threads. If your data has 1024 elements and your workgroup size is 64, you need to dispatch 16 workgroups, not 1024. The formula (data_length + workgroup_size – 1) / workgroup_size handles this correctly even when the data length is not a perfect multiple of the workgroup size.

The second common mistake is forgetting to add the COPY_SRC flag to the storage buffer and COPY_DST to the staging buffer used for wgpu buffer readback. wgpu enforces buffer usage flags strictly and will panic at runtime if you try to use a buffer for a purpose not declared at creation time.

The third mistake is forgetting to call device.poll after map_async, which results in the callback never firing on native platforms. The async model of wgpu buffer readback requires polling to drive progress on non-browser targets. On WASM targets the browser’s event loop handles this automatically, but on native Rust you must poll explicitly.

Conclusion

wgpu compute in Rust gives you a clean, safe, and cross-platform path to GPU-accelerated computing without the vendor lock-in of CUDA or the sharp edges of raw Vulkan. The key concepts to retain are, the two-buffer pattern for wgpu buffer readback using a storage buffer and a staging buffer, the importance of choosing a sensible workgroup size in your WGSL compute shader, and the performance value of minimizing CPU-GPU transfers by batching GPU work. Once you have these fundamentals working, you can scale up to much more complex compute pipelines, including multi-pass algorithms, atomic operations, and shared workgroup memory, all within the same safe Rust programming model that makes wgpu one of the most productive GPU programming environments available today.

You may also find our article on Rust for GPU Programming helpful for further reading.